John McCain’s Good Intentions Couldn’t Save America

Almost exactly ten years ago, on a crisp October night in Minnesota, John McCain stood up to his own supporters. The town hall audience said they were “scared” of his opponent, Barack Obama, who they called a “liar” and a “terrorist” and an “Arab.” But McCain wouldn’t indulge in their xenophobia—he thought he would be a better president than Obama, he said calmly, but “I have to tell you, he is a decent person and a person you don’t have to be scared of as president of the United States.”

That was McCain at his best, the McCain who will be remembered after his death Saturday evening from brain cancer. That McCain was the conservative liberals could love, or at least respect, so different from the current crop of Trumpista Republicans who have taken partisanship to its ugliest depths. McCain was a war hero who endured torture as a POW in Vietnam, he crusaded on behalf of noble bipartisan causes like campaign finance reform, he adopted a daughter from Bangladesh, he maintained lifelong friendships with his Democratic colleagues. Last year, in what might have been the most important vote of his decades-long career as an Arizona Senator, he blocked the GOP’s attempt to wipe out the Affordable Care Act after objecting to the repeal’s rushed and irregular legislative process; a poll afterward found that he was more popular among Democrats than Republicans.

McCain seemed at times to be a holdover from an earlier, more earnest era, when politicians weren’t entirely beholden to their donors and really did put country over party. In the 2000s he earned a reputation as a truth-teller, a “maverick” who broke from the GOP when moved by his conscience. Though that narrative could be overhyped at times, his 2017 ACA vote proved that he really did have an independent streak that many of his colleagues lacked. That’s the first inarguable truth about McCain. The second inarguable truth is that as hard as he crusaded for what he saw as noble causes, nearly all of his efforts ended in failure.

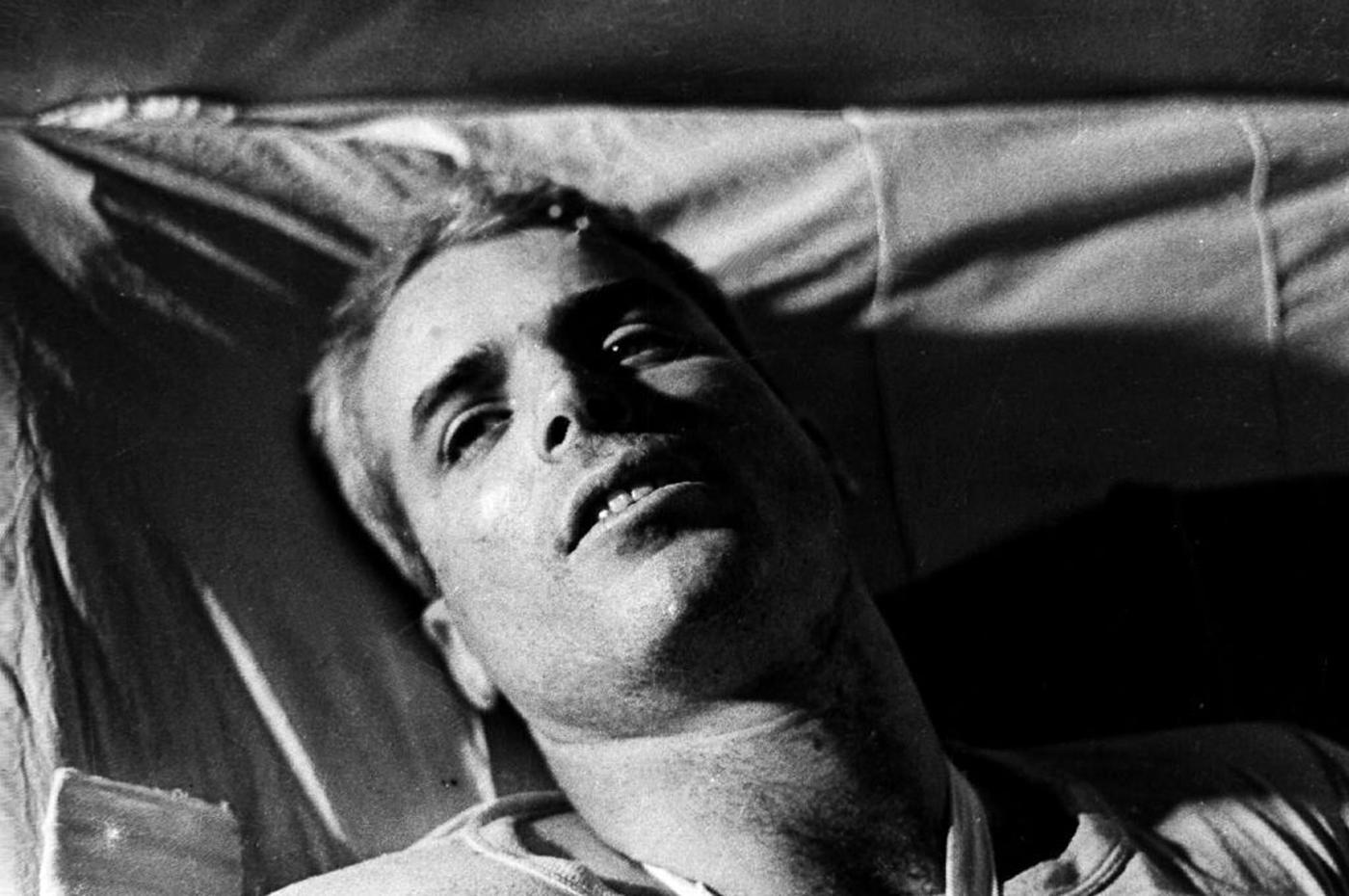

John McCain was born in 1936 on a Navy base in the Panama Canal Zone. The son and grandson of admirals, his own military career was far less distinguished, especially at its start. As a Navy pilot, he crashed one plane in 1960 and a year later flew another so low to the ground in Spain that it cut off a power line, causing a blackout. But he was allowed to continue to fly (possibly because of who his family was) and was shot down by North Vietnamese forces in 1967. Afterward, he was captured and brutally beaten and tortured until he signed a confession to crimes against the North Vietnamese people; he remained a captive until 1973 and even years later his injuries were visible—he walked with a limp and couldn’t raise his arms above his shoulder.

In time, the brutality he endured became the bedrock of the McCain legend. When he entered politics, he made his POW experiences an important part of his story. In 1982, he launched his first campaign, for a House seat in Arizona, and was attacked as a carpetbagger because he hadn’t lived in the state long. “I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the first district of Arizona, but I was doing other things,” he told a primary opponent during a candidate forum. “As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi.”

He won that election, and the next, and the next. He was a talented and ambitious politician, staying in the House only until Barry Goldwater retired from the Senate in 1986, allowing McCain to take over his seat. Back then, McCain was no anti-corruption crusader—he was instead the subject of a 1990 Senate Ethics Committee investigation as one of the “Keating Five,” a group of senators accused of doing favors for financier Charles Keating, whose Lincoln Savings and Loan had fallen apart and cost taxpayers $3.4 billion. McCain was judged not to have done anything illegal (though he was very close with Keating), but had “poor judgement,” the committee eventually ruled.

It was partly because of this scandal, McCain would later admit, that he became an advocate for getting money out of politics. “Money does buy access in Washington, and access increases influence that often results in benefiting the few at the expense of the many,” he wrote in his 2002 memoir Worth Fighting For.

It became one of his central issues, and McCain joined with other senators, most notably Democrat Russ Feingold, to push for a ban on “soft money,” which referred to the unlimited amount of money wealthy people and corporations could donate to political parties (as opposed to individual candidates). They finally won that battle in 2002 when the McCain-Feingold bill, backed mostly by Democrats, was signed into law by George W. Bush. Banning soft money was one of the signature accomplishments of his career, along with helping to normalize relations with Vietnam.

That bill wasn’t the only time McCain fought his own party. In 1998, he authored a bill that would have raised the price of cigarettes and tried to stop tobacco companies from pushing their products on teens. (This went down in flames thanks to Republican opposition.) He also engaged in a long-running and unsuccessful effort, with Democrat Ted Kennedy, to pass comprehensive immigration reform. But what really earned him his “maverick” stripes was the 2000 presidential campaign.

McCain was a longshot for the nomination—Bush was the runaway favorite—and positioned himself as an insurgent against the worst of the GOP. He ran on a message of moderation and inclusion, speaking out against evangelical figures like Pat Robertson and declaring he wanted to “build a bigger Republican Party.” He also gave the press covering him an enormous amount of access during his “Straight Talk Express” bus tour, charming them with his candor and sense of humor. He even converting a few liberals into people who would consider voting for a Republican, as long as that Republican was John McCain.

Part of his appeal was that after eight years of Bill Clinton, who never found a scandal he couldn’t weasel out of and never heard a word whose definition he couldn’t quibble over—up to and including “is”—the idea of honesty seemed almost radical to many Americans. “McCain’s résumé and candor, in other words, promise not empathy with voters’ pain but relief from it. Because we’ve been lied to and lied to, and it hurts to be lied to,” wrote David Forster Wallace in Rolling Stone during the campaign. “Who wouldn’t fall all over themselves for a top politician who actually seemed to talk to you like you were a person, an intelligent adult worthy of respect?”

If McCain had somehow beaten Bush in 2000, maybe the world would be very different. He might have convinced a lot of Democrats to switch sides in the general election and beaten Al Gore, he might have then pushed the GOP in a more moderate direction, maybe the Tea Party and Trump never would have happened. Instead, his campaign was kneecapped by incredibly dirty tactics in South Carolina, where flyers featuring pictures of his adopted Bangladeshi daughter accused him of fathering a child with a black woman he had an affair with. The Bush campaign said it had nothing to do with the flyers, but it was evidently willing to appeal to bigots, with Bush appearing at Bob Jones University, a school that at the time banned interracial dating.

In the 80s, McCain had been a rock-ribbed conservative who as a member of the House voted against making MLK Day a holiday (a vote he later regretted). But after he lost to Bush he began to take more and more positions that put him at odds with his party. He voted against the Bush tax cuts, righteously opposed the administration’s use of torture, supported a patients’ bill of rights as a way to help people fight insurers who denied them treatment, and was more willing than almost any other Republican to take measures to fight climate change. He also was one of the most impassioned supporters of the Iraq War—which he called a “mistake” in a book this year—but in 2004 he was seen as independent enough that Democrat John Kerry asked him to be his running mate (McCain refused).

The McCain of that era is the McCain of liberal fantasies: a curmudgeon who had anger issues but was ultimately good-hearted, a conservative who you could compromise with, the sort of statesman America would like to believe it produces regularly. But if you thouhgt McCain as one of the last politicians in the country possessed by real principles, the version of McCain that ran for president in 2008 seemed to tear that vision down.

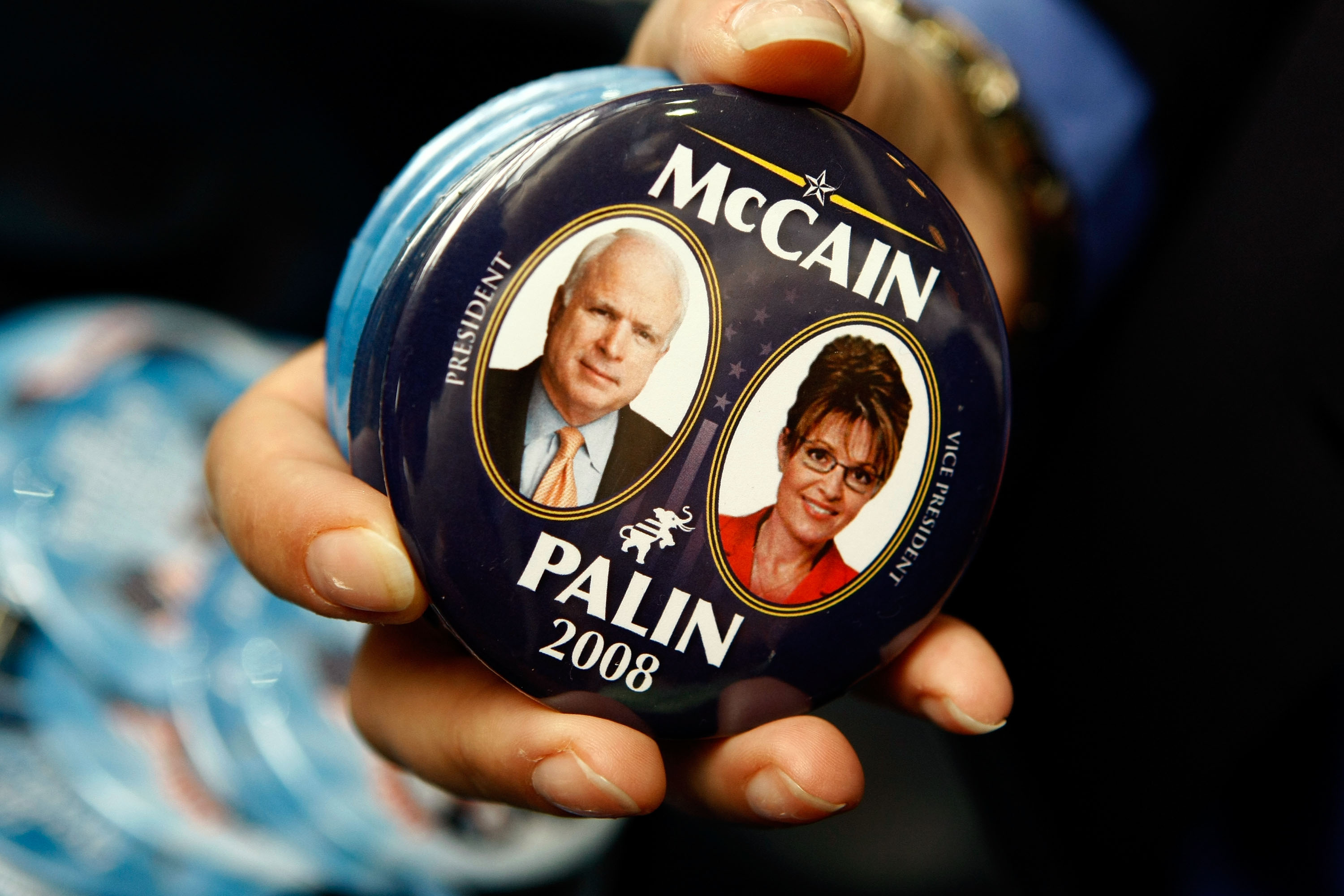

This time McCain won the nomination, but in the process cozied up to deep-pocketed interests and tilted hard to the right. As the New Yorker reported at the time, he ran a divisive campaign that questioned Obama’s patriotism—his running mate Sarah Palin said the Democrat was “palling around with terrorists”—and many of those who held up McCain as a uniquely honorable politician were disappointed with him. Colin Powell, Bush’s secretary of State, went from being a possible McCain running mate to endorsing Obama.

That October night in Minnesota when he called Obama a “good man” is remembered as a moment McCain stood up to bigotry. But it was bigotry his own campaign helped fan. Senator Lindsey Graham told the New Yorker that McCain told him, “It is not my goal to run this race and be admired as the maverick that lost.” Instead, he just lost.

Afterward, he didn’t pivot back to the center but moved further toward the hard right. He helped block a bill that would have overturned the ban on gay people serving openly in the military, seemed to reverse his previous position on climate change when he opposed cap and trade legislation, and flipped from being a moderate on immigration to demanding that a “dang fence” be completed on the border. Those moves may have helped fend off a primary challenge from the right in 2010, but at a steep cost.

“He seems to be sacrificing some of the principles he holds dear,” a former staffer told Vanity Fair in 2010. “He seems to be making compromises he wouldn’t have made ten or 15 years ago.”

McCain’s presidential defeats, the only times he ever failed to win the office he ran for, were his most obvious losses, but there were other, deeper failures. The central tragedy of McCain’s career is that his noble intentions resulted in no lasting change and his principles were ignored by the party he spent his life supporting. The bill he wrote with Feingold stopped soft money, but that victory now seems minuscule with campaigns now flooded by dark money given not to parties but to even less accountable PACs. (State and local parties have also been weakened as a result.) That tobacco bill went nowhere. Neither did all those causes he sided with Democrats on during the Bush years—they attracted too much opposition from the right. And though he tried again to pass immigration reform in 2013, that effort failed, again because of conservative opposition. In his last book, published this year, McCain wrote that the lack of movement on immigration was “a harder disappointment than other defeats have been because first, it’s something that most Americans want, and most members of Congress know is the right thing to do.”

In his final year McCain talked openly about his regrets. He admitted he shouldn’t have picked Palin in 2008, saying centrist Democrat Joe Lieberman would have been a better option. By elevating Palin, McCain indirectly helped fuel the Tea Party movement and the right-wing extremism that gave us Donald Trump. And when it came to Trump, McCain’s backbone seemed to abandon him during the 2016 campaign. Even after Trump insulted him for his time as a POW, McCain endorsed Trump, rejecting him only after the “grab ’em by the pussy” tape surfaced. And even then McCain, like all elected Republican leaders, refused to endorse Hillary Clinton—instead, he went on talk radio and vowed to block all her court nominations if she won.

After the election McCain did speak out against Trump, especially when it came to foreign policy. But like most Republican senators, he also voted with Trump most of the time, the notable exception being that famous thumbs-down vote on ACA repeal. Not that he could have done much to effectively oppose Trump. He obviously had no pull in the White House, and in 2017 was one of the least popular senators in the country according to a Morning Consult poll.

If the sort of reach-across-the-aisle politics McCain practiced at the peak of his maverick period were ever popular, they have now been nearly entirely wiped out. Bipartisan bills are occasionally written, but no one has any faith that a compromise on an important issue will become law with Trump in the White House and Mitch McConnell running the Senate. The far-right evangelicals McCain called “forces of evil” in 2000 (supposedly as a joke) are today one of the most powerful factions of the GOP and were instrumental in electing Trump. Congress is more divided and dysfunctional than it was when McCain entered it. Campaign finance reform seems more important than ever, but Republicans are more opposed to it than ever—the 2016 GOP platform called for the repeal of McCain-Feingold. It’s doubtful that any politician of either party could earn the respect of both Democrats and Republicans as McCain did for that fleeting moment in 2000, when the world was so different.

McCain is not to blame for the world we have now. However inconsistently and sometimes hypocritically, he spoke out against some of the worst aspects of the political system—there was a reason Democrats were drawn to him in 2000. But if his fellow Republicans heard him, they ignored him or else they shouted him down. He wasn’t a partisan hack, but he couldn’t stop partisan hacks from running the county. John McCain was not always the McCain who told a sea of angry partisans that his opponent was a good man, that the bigoted propaganda they heard was not true. But now that he’s gone, who else will confront the crowd?

Follow Harry Cheadle on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.