The Catholic Church Has No Idea How to Win Over Young People

Credit to Author: Alex Norcia| Date: Thu, 24 Jan 2019 19:47:24 +0000

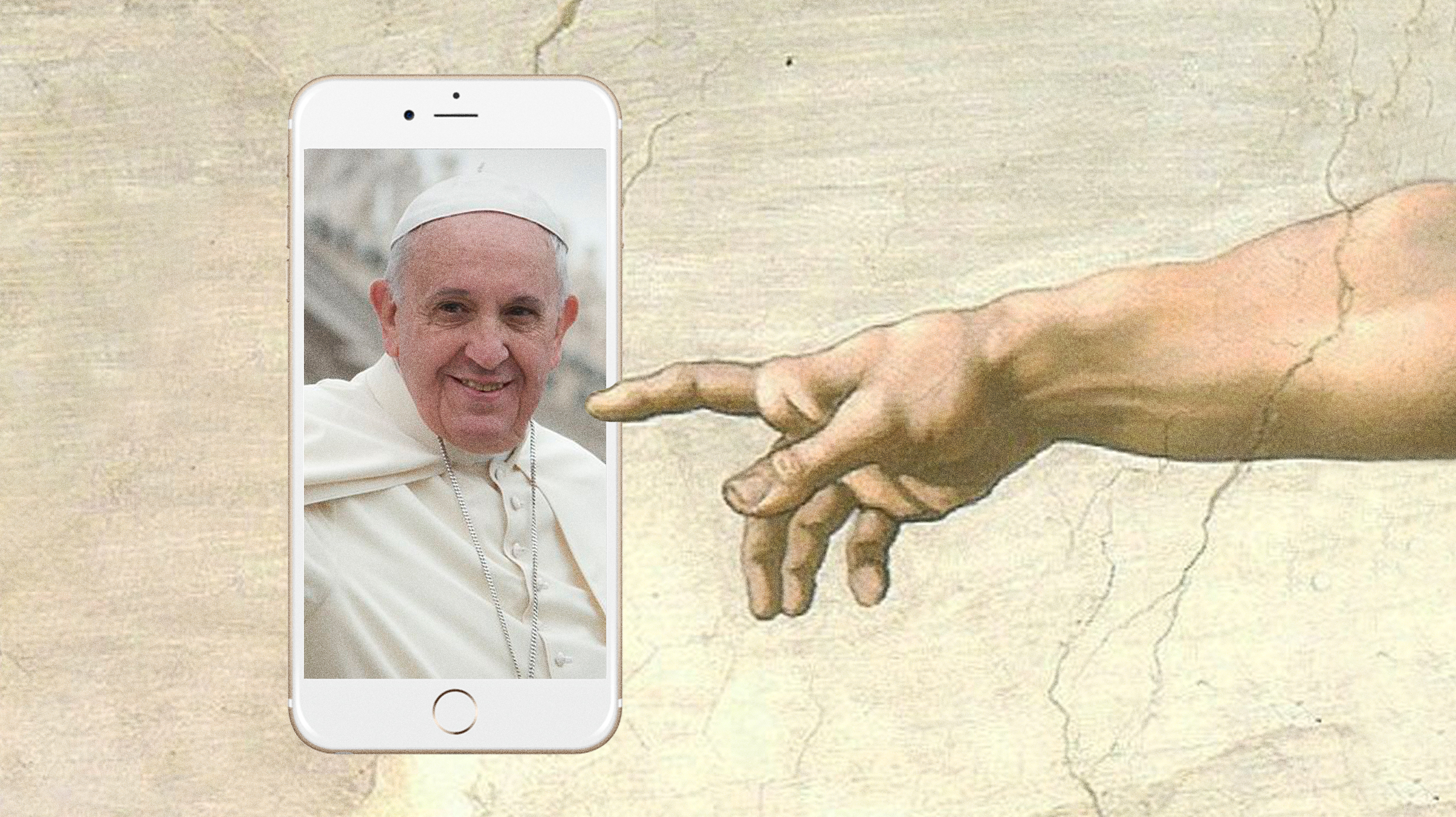

A photo circulated this past weekend of the most powerful religious leader on the planet struggling with an iPad. The device was being propped up for Pope Francis by Father Frédéric Fornos, the international director of the nearly 200-year-old Pope’s Worldwide Prayer Network, who looked on with a knowing, if less than ecstatic, smile. It’s a facial expression you might recognize as your own upon resetting your grandmother’s WiFi. The picture was also a little jarring: It seemed to illustrate how the oldest church in the world was grappling, painfully, with modernity. It alluded to the archaic practices of an institution increasingly behind the times, one more troubled than ever by its own insularity and inability (or unwillingness) to change.

Days before he jetted off to Panama for World Youth Day 2019, the iPad-armed pope urged the crowd below him in St. Peter’s Square to download and use the Vatican’s interactive app, Click to Pray. It was an initiative originally launched under the purview of the Prayer Network, which, according to its site, “addresses the challenges facing humanity and assists the mission of the Church.”

“The internet and social media are a resource of our time,” the pope said in Italian, showing off his own profile and specifically asking “young people” around the world to pray along with him. (It’s available in at least six major languages.)

This was not a subtle endorsement from the pontiff—nor was it that slick of an attempt to make the faith attractive to millennials and Generation Z. Though the software has technically been around, in some capacity, for years, this was the pope’s most aggressive nod yet for the youth to take advantage of the Church’s willingness to go digital.

“If anything, this is sort of a relaunch with the Holy Father drawing more attention to it,” Reverend William Blazek, the regional director for Canada and the US for the Worldwide Prayer Network, told me. “He’s really, now, foregrounded it.”

One can’t help suspecting the Church was ready to “foreground” literally anything to shift attention from its festering sex abuse nightmare. But the Catholic Church has been so consistently embroiled by its predatory clergy scandal over the past year that far less has has been said about its urgent need to engage young people—not only to try to stop them from leaving the faith, but to encourage nonbelievers to join as well. A hundred high-ranking bishops will meet for a Vatican summit in February to discuss the ongoing sex abuse crisis, but Francis also has to deal with an ever-increasing shortage of priests and the lack of religiosity among younger generations, as well as declining trust among US Catholics in particular.

Except winning over followers while addressing a crisis has proven even more difficult for Francis than it might have any other pope because his approach, as with other issues like gay rights and divorce that have broadly been accepted in society, must be catered toward both the conservative and liberal factions within a bitterly divided faith.

“There is an important difference between the right and the left in the Church,” John Portmann, a professor of religion at the University of Virginia, stressed to me on the phone. “So you do have young people flocking to the Church, but these kids want the Church to go on in very traditional ways. And then, on the other hand, you have Catholics [who are much more progressive] like Lady Gaga.”

There’s the added dilemma of how the Church appeals to an estimated 1.3 billion followers across the globe who have such varied cultural, political, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Massimo Faggioli, a professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University, explained that it’s much easier to see the Church’s marketing plan for the United States—what he labeled an “Evangelical Catholicism,” with its likeness to “a style of prayer and a theological culture that is culturally closer to American Evangelical Protestantism”—than it is to make sense of it in Europe or elsewhere.

Attempting to strike a balance between these competing interests leaves Francis in an awkward place, where his best bet is apparently to release a seemingly innocuous piece of software that looks more like desperation than a plan. (It’s actually already been used by trolls to, say, pray for the Instagram egg and their deceased hamsters.)

The premise of the Vatican’s (free) Click to Pray app is exactly what it sounds like. It works much like other social platforms, so as a user, you can post prayers yourself, respond to strangers’ prayers (comment or “click to pray,” which is essentially “favoriting” them), or scroll through the prayers that others have posted online without having to actively engage in them. (When I logged on the other night, I saw calls in English for both an end to world suffering and a man’s crude plea for his neighbor to find him attractive.)

According to the Vatican’s website, “Click to Pray has three main sections: ‘pray with the pope,’ with the pope’s monthly prayer intentions for the challenges facing humanity and the mission of the Church; ‘pray every day,’ with a prayer rhythm involving three daily moments; and ‘pray with the network’ that is a space where users (Pope Francis among them) can share their prayers with the others.”

It isn’t the Vatican’s first shot, of course, at capitalizing on the world wide web. After all, Francis is already on the internet, making his mark in a culture where Donald Trump is blasting out vaguely official threats and US congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the 29-year-old Democratic Socialist from the Bronx who has embraced social media without phoniness, is teaching her party how to tweet. The @Pontifex handle has nearly 18 million followers, and, yes, he’s also on Instagram. In 2017, Francis reportedly had more of a Twitter following even than Trump. He releases a monthly video, the “Pope Video” (also under the auspices of the Prayer Network), as well—and it all adds up, Reverend Blazek argued, to a “communications package.” The pope’s video this month, tellingly, was called “Young People and the Example of Mary.”

Juan della Torre, the CEO and founder of the Argentina-based digital firm La Machi, the designer of Click to Pray, explained via email that this has been a piecemeal rollout over a period of years. (In addition to other faith-related projects, some of the company’s other clients appear to have included a national park; illustrations involving “great beards”; and Medical Hair, which has “specialists in capillary micro-transplant hair by hair, the definitive solution to scientifically proven baldness.”)

All of which is to say pivoting to apps isn’t shocking in the larger context of the Church’s demonstrated willingness to use relatively new technology to spread the gospel.

“The Church is usually slow in accepting change, but that’s not true when it comes to mass media,” Faggioli emphasized to me over the phone. “Historically, if you go back to the development of the printing press, or newspapers and magazines in the 19th century, or the radio in the early 20th century, or the movies in the 1920s and 30s—the Vatican has always been eager to use new ways to communicate.”

There’s a “pragmatism,” Faggioli added, from the Vatican and its embracing of technology—the primary reason being that it allows for the easy dissemination of the Word of God.

Questions remain, however, about just how technologically savvy the Church is willing to get, even if CBS executives are green-lighting shows about God possibly having a Facebook page. Confession, for instance, cannot technically be taken on the internet.

“Catholicism is a faith centered on the mass, where the body and soul and the senses are as important as the mind,” writes Andrew Sullivan in a recent New York Magazine cover story on gay priests. “The mass is, in some ways, a performance.” Sacraments, such as the Eucharist (in Catholicism, a priest literally converts a cracker and wine into the body and blood of Christ), involve a physicality that’s hard to imagine in the digital realm.

“For years, we’ve had ‘mass for shut-ins’: Catholics who can’t make it to a church for mass can just watch on TV,” Portmann said, when I asked him about the relationship between technology and the Church. “Catholics who miss mass without a good excuse commit a mortal sin; many Catholics who can’t make it to mass worry about that. The televised mass ‘counts’ as going to mass. What the pope is doing by blessing Click to Pray might be seen as undermining the importance of a real presence.”

The Church is unlikely to discover immediate, sweeping success with this surface-level solution, either. It’s something of a shot in the dark—arguably part of a pattern of quick, not very well-thought-out decision-making that’s been criticized as of late. (“As far as can be seen at present, the meeting is not well-prepared,” wrote one religion reporter, in discussing the upcoming Vatican summit on sex abuse.)

“I checked it out, and I am not thoroughly impressed,” Brother Javier Hansen, one of three US delegates to the Synod of Bishops of Young People, Faith, and Vocational Discernment, wrote to me in an email, saying that he had not heard of anybody using it and referencing other Catholic-targeted prayer apps, like Laudate. (Brother Hansen said he leaned relatively conservative, and still practiced mass in the pre–Vatican II Latin form, with what he described as a “a contingent of young people.”) According to della Torre, “so far, Click to Pray had more than 415,000 downloads worldwide.”

“I strongly believe the two issues are related: sex abuse and the release of this new prayer app,” he continued. “I believe the Vatican is trying to refocus our attention as the credibility of Francis plummets.”

The Vatican, in other words, will have to spend a long while if it’s to adequately confront its past mistakes while keeping its diverse flock even remotely unified.

Christian Smith, a professor sociology at the University of Notre Dame and the author of Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers, was careful to point out that, even before the sex abuse scandal, young men and women in America had been fleeing religion for decades. Former Catholics were prompted by forces, he described, that were “multiple and long-term”—among them that they think the Church “does not offer them anything unique that they particularly need, and that its teachings are simply outdated and irrelevant”; that, for them, “the Church is just way in outer space on sexual ethics”; and that the “Church’s core metaphysical worldview is based on supernatural and sacramental realities, that just do not fit the deep, reigning cultural assumptions of materialism, mass-consumer capitalism, scientism, secularism, and postmodernism.”

In short, initiatives like this one may be way too little, too late.

“If leaders in the Church think that improving its interface with digital technology is going to help it stop hemorrhaging youth, they are sadly deluded,” Smith wrote me. “It’s a gimmick, and a desperate grasping at straws. To call this a Hail Mary pass is way optimistic.”

“What it shows,” he added, “is how out of touch so many Church leaders really are.”

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Alex Norcia on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.