I Spent Months in the Parts of Lisbon the Government Tries to Hide

Credit to Author: Tiago Figueiredo| Date: Mon, 18 Feb 2019 17:38:14 +0000

This article contains sensitive images.

This article also originally appeared on VICE Portugal

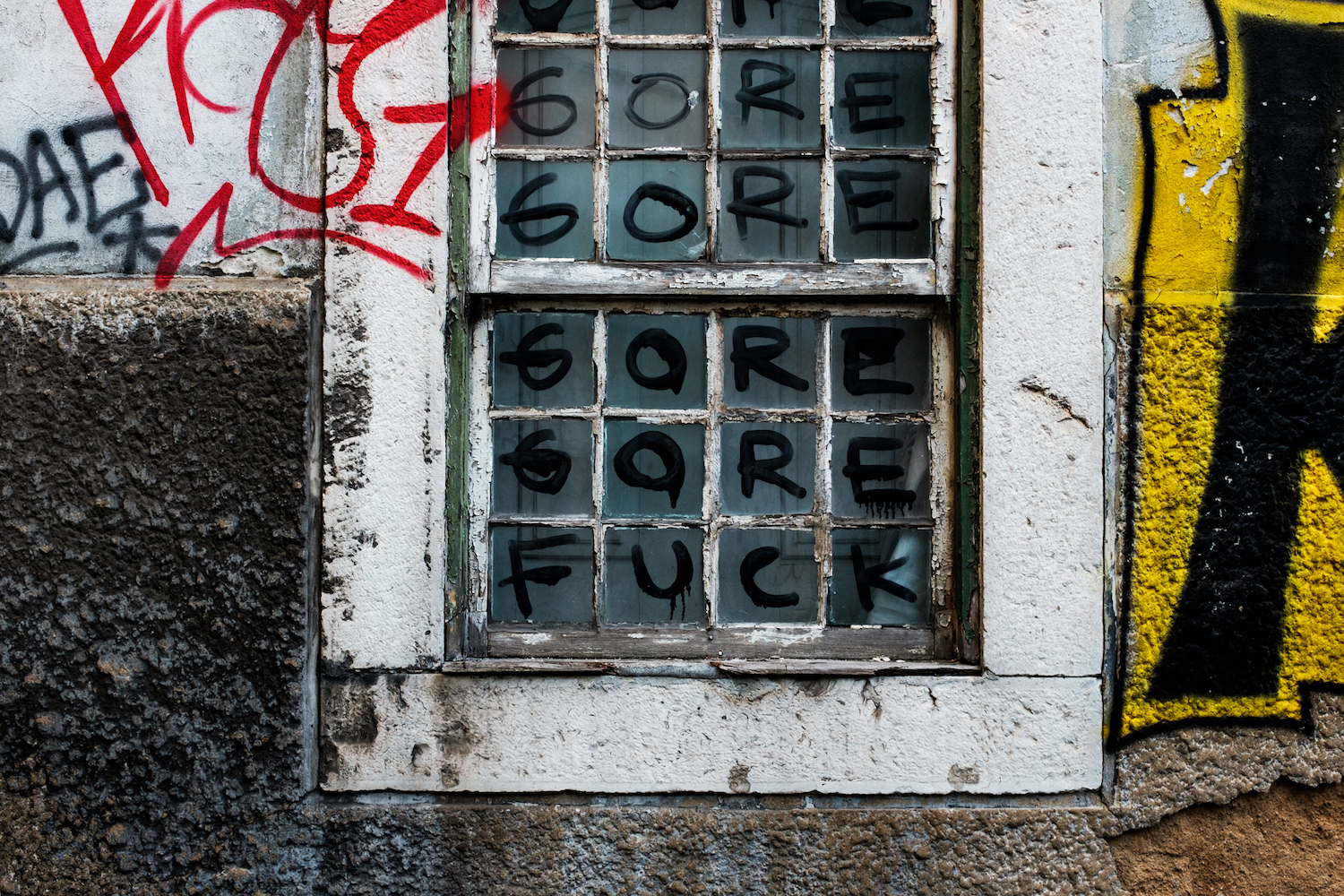

Intendente is one Lisbon’s oldest neighbourhoods. The area is strongly gentrified, with a lot of tourists wandering the streets. But behind the new bars and investment banks that have forced longtime residents to the edge of the city exists a very different reality that the government seems determined to hide.

In the 1960s, Intendente became famous for its extremely liberal vibe. First came the bars, then the sex workers and finally the crackdown. On the 8th of August 1977, the newspaper A Capital reported that 1,313 sex workers between the ages of 16 and 24 had been arrested in Lisbon in the first half of the year alone.

The crackdown eased over the following decades, and the number of sex workers in the area started to rise again. In the early 2000s, however, police introduced anti-drugs measures in two of Lisbon’s most notorious neighbourhoods: Casal Ventoso and Curraleira. Obviously this didn’t stop people in Lisbon from doing drugs, but simply relocated the issue. That’s when the drug scene in Intendente really emerged, flourishing in a community with a liberal core where people were ready and willing to indulge.

Then at the end of 2012, the local council decided to invest in the neighbourhood. That meant more police on the streets, as Lisbon was redesigned for tourists. Rent went up and longterm residents were pushed out of their homes and made to fend for themselves. Intendente was being bought, piece by piece, by luxury hotel chains and investment banks. The new life in Intendente didn’t completely replace the old one, it simply pushed it out of sight.

Over the course of a year, I spent time with many of the addicts and sex workers struggling to survive in this alternate reality, to get to know them and better understand the lengths the government goes to pretend they don’t exist.

Soraia

Shortly after we first met, I spot Soraia walking down a popular street in Intendente. “Fuck, she looks so skinny,” a stranger standing next to me says. “She looked great when she first arrived.” I ask when that was. “Not even three months ago.”

Later that night, I meet Soraia while she’s smoking crack in a stairwell, where she had agreed to let me hang out and photograph her with her friends. But a few days later, she’s not so welcoming, as she and a mate walk down the Largo do Intendente – a popular square in central Lisbon, full of new developments.

“Can I join you?”

“Where?”

“Wherever you’re going.”

“We’re going to a room.”

“That’s OK, I’d like to come along.”

“It’s not going to happen. Sorry.”

They keep on walking, eventually crossing the street to meet a waiting man. The three of them get in a taxi and speed away down the avenue.

But then, at the end of one particularly frustrating day, when I haven’t been able to take a single photo, I see her again. It’s 2AM, and as I’m walking home, she’s walking straight towards me. She’s annoyed too – she hasn’t had a single client all night.

She’s warmed to the idea of chatting to me, so I suggest we head to one of the nearby motels that welcome Soraia and her clients, so I can photograph her in the actual environment she works in. When we get there, Soraia rings a bell, the doors unlock and we walk up a flight of stairs taking us through to a dark hallway with a reception desk. She tells me to hand over €5 for the room. The woman behind the desk reaches out to grab the money before sliding over a key. “You have an hour.”

Soraia leads the way. “Do you mind if I smoke?” she asks when we get to the room – which she does, after taking her clothes off. Crack helps her to not feel, she says. But that also depends on the quality of the cocaine. When it’s too diluted, she says, her high often ends before the client’s done.

“I never thought I’d be where I am,” she confides. “For years I smuggled drugs into Spain, and never once did any. I saw women in the state that I am in now, saw all the disgrace that comes with drugs, and never thought I’d fall in.”

Soraia was born in Portugal, but was raised by her grandmother in Spain. Thanks to a rebellious phase and a string of shit boyfriends, she joined a network of drugs and weapons smugglers. For a while she worked in Germany, arranging fake weddings for Eastern European immigrants. Now she’s back in Portugal, where she has a son who’s being raised by relatives on the outskirts of Lisbon.

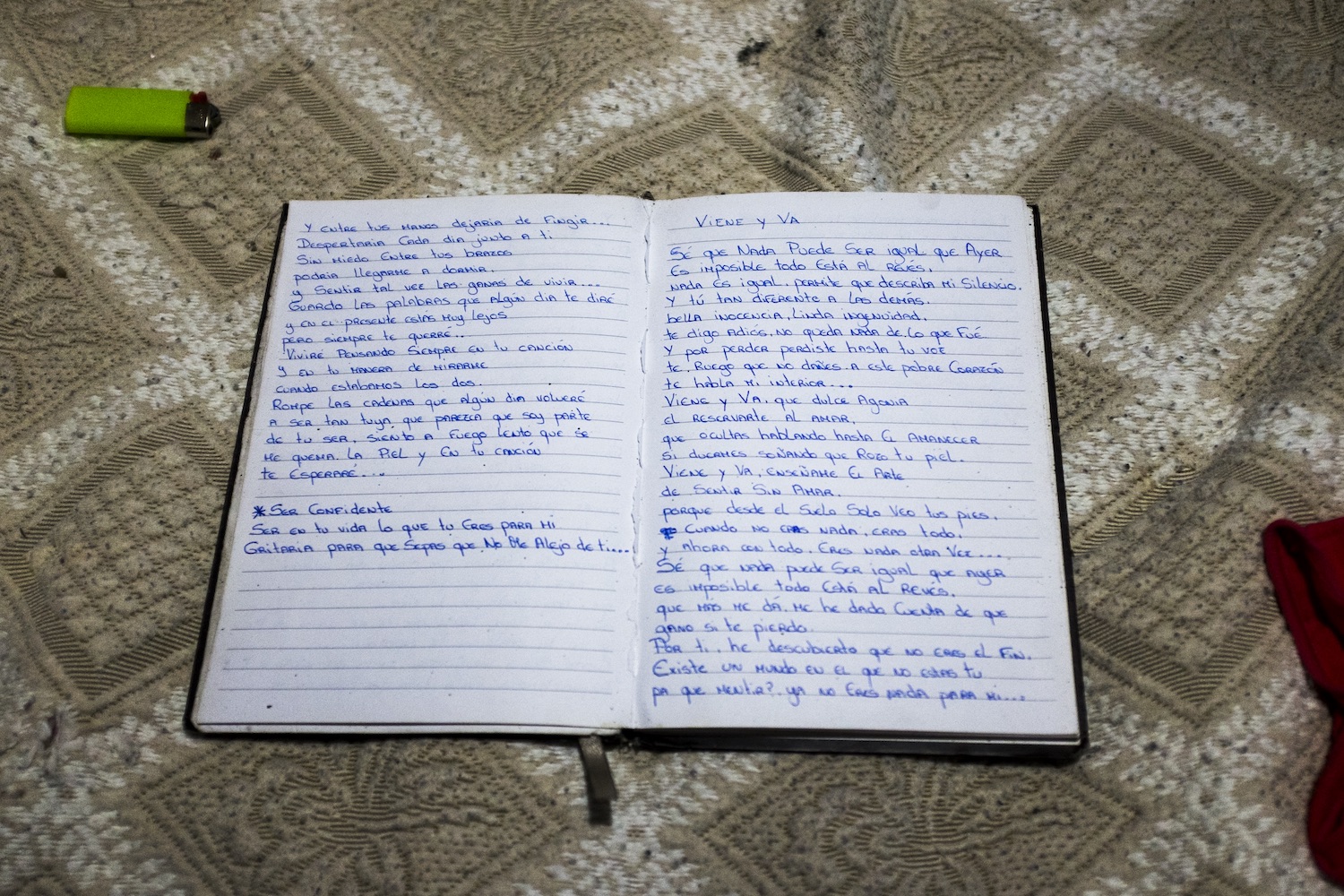

On the notepad that Soraia has just used to prepare her hit, she keeps poems and lyrics she’s written in Spanish. She reads aloud from her favourite poem, “Viene y va” (Come and go).

It hasn’t been an hour yet when someone knocks on the door. I hear the receptionist shouting that we have to leave because our time’s up. Soraia nervously starts to pack up her pipe and penknife. “Please don’t open it yet,” she asks. “They can’t find out we smoked inside.” I stall by shouting back that our time isn’t up, that it hasn’t been an hour. Moments later, Soraia is dressed and ready to go. When I unlock the door to walk out, the receptionist is standing there with another woman and a man. “Don’t ever come back,” the receptionist screams, as Soraia walks away.

A few days later, Soraia takes me to her home – an abandoned house that she shares with ten other people, located on one of the steepest streets in the neighbourhood. To get in, you must squeeze between the bars of a gate then move the wooden board acting as a makeshift front door. The house is full of remnants from a construction site that was put on hold, such as buckets and a concrete mixer.

Soraia says she’s struggling a bit today. One of her fellow squatters is in love with her, and has asked her to be his girlfriend. She told him she wasn’t interested, so out of spite he decided to rip up her clothes. All of them.

Erineu

Erineu is sitting on the steps of a bar that’s shut. He’s focusing on a pipe made out of a bottleneck. He uses the spring of a pen to clean out the pipe before covering it with foil, punching a few holes in it and taking a hit of crack.

A couple of tourists walk by, looking nervous. They’re headed to Largo do Intendente square, but their map app hasn’t warned them that the shortest way isn’t the prettiest.

Later that night I run into Erineu again. He’s on his way to pick up from the Mouraria neighbourhood and asks me if I want to join him, though warning me that I won’t be able to take any pictures. The streets grow narrower and narrower, and run into tiny squares where kids play football and old men drink beer and play cards. On every street corner are young men on the lookout for the police, signalling to buyers when it’s safe to come out and do business.

Erineu takes a €10 note out of his pocket and hands it to the dealer. In return, the dealer pops a small white ball from his mouth and gives it to Erineu. On our way back, we pass by a small grocery store where Erineu pays 20 cents for a ready-cut strip of foil. The neighbourhood’s economy has adapted to the needs of its residents.

I hang with Erineu and Soraia for the rest of the day, as he constantly lights up whatever is left of the white ball. When Soraia eventually gets up to leave, she crosses paths with a guy who yells out Erineu’s name, but on seeing my camera, he heads straight for me.

“Who are you?”

“I’m a photographer, I’m working on a project…”

“Turn your back against the wall! Police!”

He flashes his badge at me and, speaking into his lapel, calls for backup.

“What do you have in your pockets?”

“My house keys…”

“Take it all out!”

I show the undercover officer my keys, phone and a few coins. He asks me to turn my phone on and off to prove it’s real. After I do, he gives it all back to me. “Go away, I don’t want to see you again,” he shouts. I explain that I’m allowed to take pictures here and that I’m not doing anything illegal, but he’s not having any of it. “Did you hear what I said? Get the fuck out of here. It’s for your own good. Go photograph something else, I don’t want to see you here.” I walk away humiliated, and a bit embarrassed that I had just left Erineu alone in that situation. The next day, I head back to find Erineu to see if he’s okay and try and understand what happened. “It’s all good,” Erineu says. “But, who is he and what does he want?” I try and push with no joy. “It’s all good.”

Anabela

Anabela had it all. She grew up surrounded by luxury and privilege in a poor country that was just waking up from a 48-year dictatorship. As we drink whiskies in a bar, she describes the rides in her family’s convertible, sailing around the Med and the high-end coke at society parties. But then came the divorce, and with it she fell away from that scene – losing her fancy surname and an ability to afford the expensive vices she had become accustomed to.

Despite her monied past, one thing is clear as we speak: Anabela can take care of herself in this new world, and she knows it. The 50-year-old is trained in martial arts, she says – flexing her muscles to prove it – and isn’t afraid to intervene if things kick off wherever she is.

Several weeks later, I recount the story of how I almost got arrested, adding that I bumped into the same officer on another night, arms crossed as he stood over a line of addicts. I watched him lean down to pick a cigarette off the floor before suddenly kicking it away, which really scared one of the junkies. That was when the officer looked up and recognised me. “Didn’t I tell you to never photograph here again?” he said. “I can tell by the look in your eyes that you don’t belong here and you’ll end up getting yourself killed. I don’t want to see you again.”

Anabela smiles. “I didn’t tell you this when we first spoke because I didn’t know who you were,” she says. “That guy does business in the neighbourhood. He shows up from time to time and disappears when he gets into trouble. He lived in Canada, so they call him ‘The American’. He told me all about the night he pretended to be a cop; he was laughing really hard over how scared you were. He also said he would take your camera away if he saw you again, but I doubt he meant it.”

Anabela picks her clients carefully, usually relying on an established list of regulars that have her number and sometimes book her up for entire weekends at a time. Once, a single session lasted for over 10 hours because her client had taken Viagra. It only ended when she told him he had to stop. A few days ago, Anabela was with a married client who videoed their time together just so he could show his wife later.

She says she can make as much as €400 on one of those scheduled weekends. In my time here, I’ve learned that the rate women charge for their work in the neighbourhood varies wildly. I’ve met teenage girls new to the neighbourhood who charge €25, while some will go as low as €10 when they become desperate for a hit. One afternoon as we’re chatting, Anabela’s mate storms up to us pissed off and offended. A potential client had just offered to pay her €7.50.

A few days later, I meet another sex worker, who’s leaning against a wall drinking sherry. When I approach her, she doesn’t give away her name and tells me that she’s not looking for clients today; she’s just here to have a drink and see some friends. After reassuring her that I just want to chat about life in Intendente, she agrees – as long as I pay for the room.

She used to work two jobs, but after she lost one of them, she came very close to losing the house she lived in with her son. She tells me that the drinking helps her through most days, but unlike many of her colleagues, she hasn’t moved on to crack.

Later, I’m going into another motel to photograph a 19-year-old woman who had to leave home with no means of survival for what she calls “family reasons”. As we walk in, an older sex worker steps out at the same time. “Oh, you’re working here too?” she says to the girl. “I had seen you around but wasn’t sure. You’re so young,” she adds. “Yes, I started a week ago,” the 19-year-old replies. Viene y va.

Tiago Figueiredo is a photographer based in Lisbon.

This article originally appeared on VICE PT.