EPA Projects Final ‘Good Neighbor Plan’ Will Result in 14 GW of Coal Retirements

Credit to Author: Sonal Patel| Date: Thu, 16 Mar 2023 13:23:48 +0000

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on March 15 issued the final “Good Neighbor Plan,” its latest iteration of the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR) that could require coal, oil, or gas steam power plants in 22 states to reduce their nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions levels by 50% by 2027 compared to the 2021 ozone season.

Issued under the Clean Air Act’s (CAA’s) “good neighbor” or “interstate transport” provision, the EPA’s new “Good Neighbor Plan” essentially seeks to ensure that the nearly two dozen “upwind” states will incrementally tamp down their annual emissions of NOx—an ozone-precursor pollutant—during ozone seasons that run from May through September. The effort is geared to help “downwind” states attain and maintain the EPA’s 2015 Ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), an Obama-era smog rule.

The EPA said the plan will ensure “that emissions reductions will happen as quickly as possible and be aligned with Clean Air Act deadlines for states to achieve the 2015 ozone NAAQS—which vary according to the severity of nonattainment.” The initial phase of NOx emissions reductions will take effect “as soon as possible” to meet the Aug. 3, 2024, attainment date for areas classified as “moderate attainment.” However, more emissions reductions will be required at the beginning of the 2026 ozone season to meet the Aug. 3, 2027, attainment date for “serious” nonattainment areas, it said.

But while agency officials during a press briefing on Wednesday underscored the rule’s benefit to public health and welfare, they noted the rule could force significant changes at some plants, including generation shifting, pollution control installations, or retirements.

According to a regulatory impact analysis (RIA) affiliated with the rule, the agency projects the final rule will result in an additional 14 GW of coal retirements nationwide—constituting a reduction of 13% of national coal capacity. The agency estimates compliance costs could hover at $1.3 billion by 2030, though it said estimated health benefits ranging from $3.4 billion to $15 billion and climate benefits of $1.5 billion far outweigh those costs.

First Standards for Industrial Sources

Beginning in the 2026 ozone season, meanwhile, the EPA set enforceable NOx emissions control requirements for existing and new emissions sources in industries that are estimated to have impacts on downwind air quality. The standards mark the first time that the agency has imposed emission budgets on sources other than power plants pursuant to its authority under the “good neighbor” provision.

Industrial sources the agency highlighted include reciprocating internal combustion engines in pipeline transportation of natural gas, kilns in cement manufacturing, reheat furnaces and other furnaces in steel mills and glass manufacturing, and boilers in several industries. Industries affected include iron and steel mills; ferroalloy manufacturing; metal ore mining; basic chemical manufacturing; petroleum and coal products manufacturing; pulp, paper, and paperboard mills; and solid waste combustors. The EPA suggested the industrial standards would “collectively achieve an approximately 15% reduction in NOx emissions from 2019 ozone season, point source emissions.”

How the EPA Plans to Achieve NOx Emissions at Power Plants

While the EPA has rolled out several rulemakings under the CAA “good neighbor” provision since 1998, the only emissions profile from fossil-fired power plants that all its ozone-transport rulemakings have targeted has been the emissions of NOx. “Tropospheric, or ground level ozone, is not emitted directly into the air, but is created by chemical reactions between oxides of nitrogen (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOC),” the agency explains. “This happens when pollutants emitted by cars, power plants, industrial boilers, refineries, chemical plants, and other sources chemically react in the presence of sunlight.”

Along with tightening ozone NAAQS, the EPA has sought to reduce ground-level ozone pollution by regulating interstate air pollution transport, mainly through allowance trading programs. Currently, the agency administers six CSAPR trading programs for power plants that differ in pollutants, geographic regions, time periods, and in levels of stringency.

The agency’s new “Good Neighbor Plan” essentially defines NOx emissions performance obligations for power plants in 22 upwind states through federal implementation plans (FIPs). To fulfill those obligations, the plan implements another allowance-based trading program based on revisions of the CSAPR NOx Ozone Season Group 3 Trading Program. The trading program will begin in the 2023 ozone season (which runs from May 1 through Sept. 30).

The 22 states where power plants will be required to meet emissions reductions under FIPs include Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Power plants covered by the FIPs and subject to the budget include fossil-fired plants of more than 25 MW. “For 2023, total ozone season NOx emissions reductions of 10,000 tons are from [electric generating units (EGUs)]; for 2026 total ozone season NOx emissions reductions of 70,000 tons are from EGUs and non-EGUs, and for 2030 total ozone season NOx emissions reductions of 79,000 tons are from EGUs and non-EGUs,” the EPA’s RIA says.

So far, only 12 states have been required to participate in the Group 3 trading program (Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia). The new final rule will amend these states’ FIPs in accordance with revisions to the Group 3 trading program regulations, the EPA said.

The Plan Requires ‘State-of-the-Art’ NOx Reduction Technology Considerations

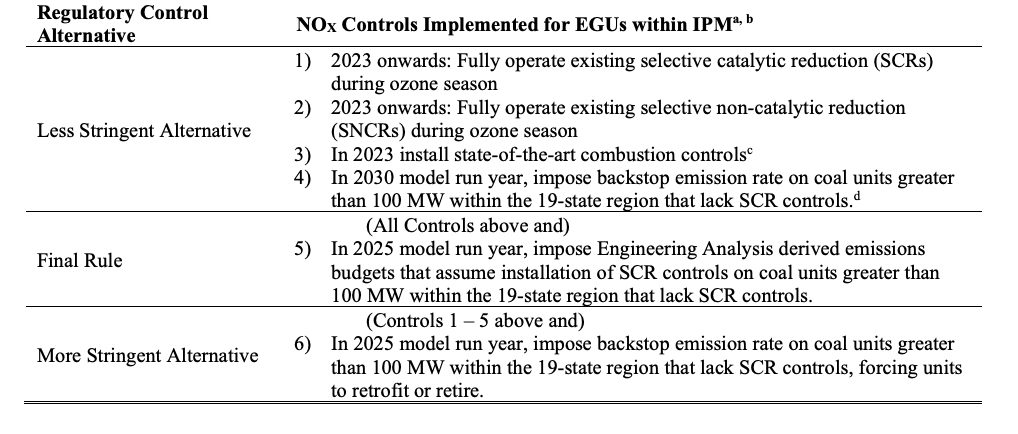

In order to achieve emissions reductions as soon as possible, the EPA set an “initial control stringency based on the level of reductions achievable through immediately available measures.” For the 2023 ozone season, at least, these include “fully operating and optimizing existing” selective catalytic reduction (SCR) units and existing selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR) units.

However, “in order to achieve the remaining needed emissions reductions from power plants, the final rule sets emissions budgets that decline over time based on the level of reductions achievable through phased installation of state-of-the-art emissions controls at power plants starting in 2024,” the agency noted. In the plan, examples the agency provided of “state-of-the-art” NOx combustion controls include low-NOx burners (LNB) and over-fire air (OFA). These technologies will be “available” by the beginning of the 2024 ozone season and can be installed or updated quickly, the agency suggested.

“The EPA finds that, generally, the installation phase of state-of-the-art combustion control upgrades—on a single-unit basis—can be as little as 4 weeks to install with a scheduled outage (not including the pre-installation phases such as permitting, design, order, fabrication, and delivery) and as little as 6 months considering all implementation phases,” it noted. It also added, “The EPA estimates that the representative cost of installing state-of-the-art combustion controls is comparable to, if not notably less than, the estimated cost of optimizing existing SCR (represented by $1,600 per ton).”

As significantly, the agency added that it made a finding that “the required controls provide cost-effective reductions of NOx emissions that will provide substantial improvements in downwind ozone air quality to address interstate transport obligations for the 2015 ozone NAAQS in a timely manner. These controls represent greater stringency in upwind EGU controls than in the EPA’s most recent ozone transport rulemakings, such as the CSAPR Update and the Revised CSAPR Update.” Reductions will be even more stringent by 2026 for 19 states that will be linked in 2026—Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and West Virginia.

The EPA determined that for those 19 states, the “selected EGU control stringency also includes emissions reductions commensurate with the retrofit of SCR at coal-fired units of 100 MW or greater capacity (excepting circulating fluidized bed units [CFB]), new SNCR on coal-fired units of less than 100 MW capacity and on CFBs of any capacity size, and SCR on oil/gas steam units greater than 100 MW that have historically emitted at least 150 tons of NOx per ozone season.”

“Building on the long and successful track record of EPA’s CSAPR ozone season trading program, this program will secure significant reductions in ozone-forming pollution while providing power plants operational flexibility they need to continue providing reliable and affordable electric service. The final rule’s 2027 budget for power plants reflects a 50% reduction from 2021 ozone season NOx emissions levels,” the agency noted.

Along with these measures, the plan implements “a backstop daily emissions rate in the form of a 3-for-1 allowance surrender for emissions from large coal-fired units that exceed a protective daily NOx emissions rate,” the agency said. “This backstop would take effect in 2024 for units with existing controls and one year after installation for units installing new controls, but no later than 2030.”

The plan will also annually recalibrate the size of the emissions allowance bank “to maintain strong long-term incentives to reduce NOx pollution.” Finally, it will annually update budgets starting in 2030 “to account for changes in power generation, including new retirements, new units, and changing operation.” Updating budgets may start as early as 2026 if the updated budget amount is higher than the state emissions budgets established by the final rule for 2026–2029, the agency said.

The Impact on Costs and Reliability

Joseph Goffman, principal deputy assistant administrator of the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation on Wednesday told reporters during a briefing call that the rule essentially leaves power plants with two choices. “Either, where they already have NOx control equipment installed to run that equipment full tilt throughout the ozone season, and where power sector sources don’t have NOx control equipment installed, the rule asked them to install that equipment.”

But the RIA suggests the impact on the sector may be more substantial. While the final rule is projected to result in an additional 14 GW of coal retirements nationwide, it could spur an incremental 8 GW of SCR retrofits at coal plants. “The rule is also projected to result in an incremental 3 GW of renewable capacity additions in 2025, consisting primarily of solar capacity builds. These builds reflect early action or builds that would otherwise have occurred later in the forecast period,” the EPA said.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan during the call on Wednesday told reporters that the EPA made several adjustments to the proposed plan, issued in April 2022 to address reliability concerns. The final plan, for example, provides greater compliance flexibility for power plants by deferring “backstop” emission rate requirements for plants that currently do not have state-of-the-art controls until no later than 2030, he suggested. It also enhances the availability of allowances during a period of relatively rapid fleet transition by allowing power plant owners and operators to “bank” allowances at a higher level through 2030.

“We have taken a lot of comment on this rule and have worked with a lot of our grid operators and our regional planning organizations that focus on managing electricity,” Regan said. “We have really prioritized reliability.”

In a dedicated fact sheet focused on the Good Neighbor Plan’s impact on reliability, the EPA suggested it also consulted with the Department of Energy, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), and other parties responsible for ensuring reliability.

The EPA added that it “hosted a series of meetings with the reliability organizations that commented on the proposal to thoroughly understand their perspectives and seek to address their concerns in the final rule.” Ultimately, the plan provides “greater certainty for grid operators and power companies by establishing a predictable minimum quantity of allowances available through 2029,” the agency said.

One of the nation’s biggest regional transmission organizations, PJM Interconnection, on Thursday confirmed it had provided feedback to the EPA on the rule’s reliability impacts. Of the 22 states affected by the Good Neighbor Plan, 10 are located within PJM’s 13-state footprint: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia.

PJM has anticipated the rule could result in the retirement of as much as 4.4 GW within its footprint. However, it noted on Thursday that “changes made in the final rule provide more time, out to 2030, for large coal-fired generators to install needed controls.” The organization added: “PJM expects to work closely with EPA and stakeholders to further the development of these reliability assurance provisions to accompany the final rule.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).

The post EPA Projects Final ‘Good Neighbor Plan’ Will Result in 14 GW of Coal Retirements appeared first on POWER Magazine.