The Wild Story of Whitaker Wright, the Con Man Who Killed Himself in Court

Credit to Author: Seth Ferranti| Date: Tue, 08 Jan 2019 14:08:45 +0000

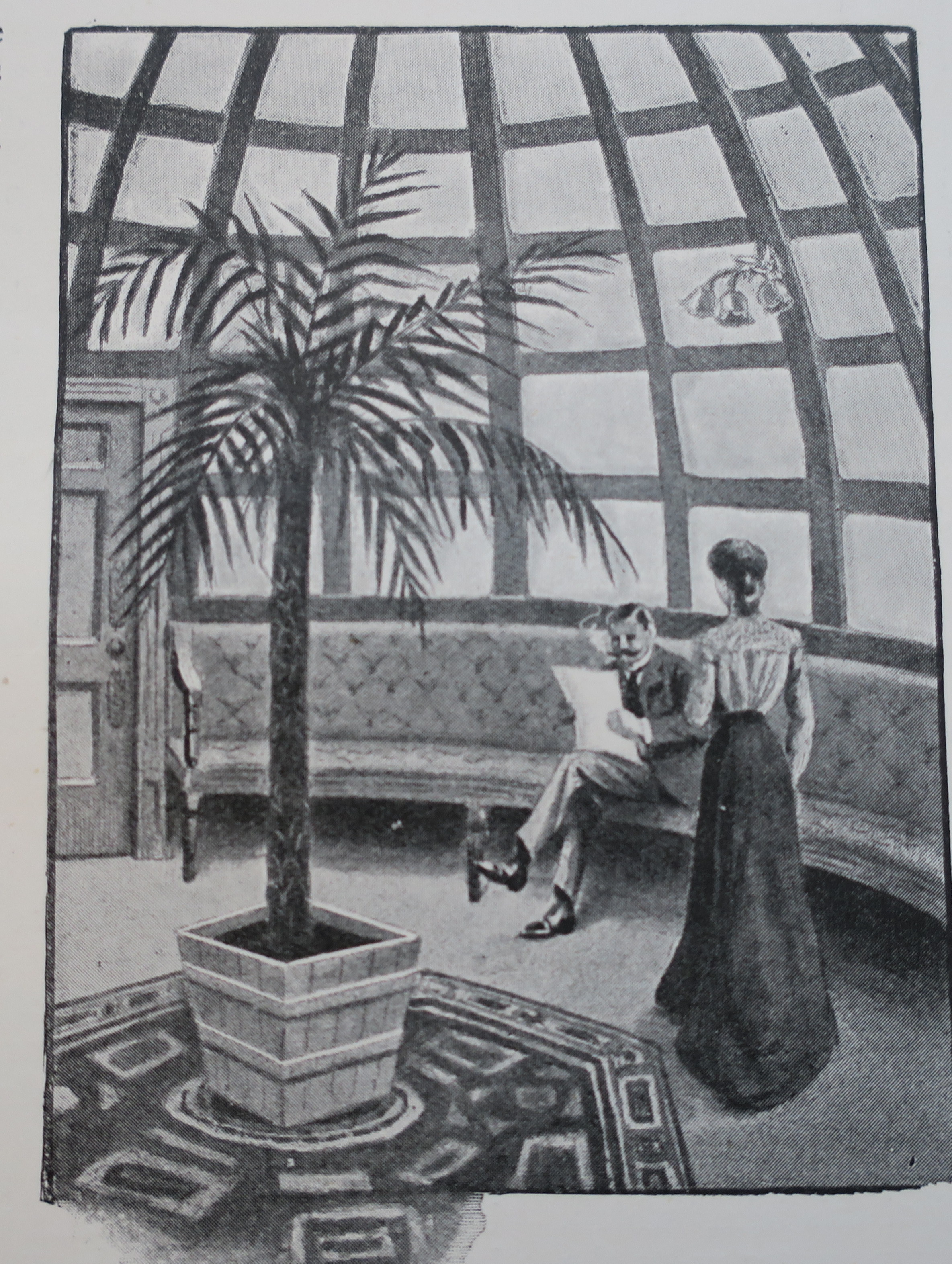

Back in the 1990s, writer Henry Macrory read an article about an underwater ballroom made of glass that had been sitting at the bottom of a lake in Surrey, England, for more than 100 years. He went to visit and, like many before him, was mesmerized. As an architectural folly, it was in a class of its own, and Macrory wondered who on earth could have built such a place, this smoking room off the mansion of a sprawling estate. He discovered it belonged to Whitaker Wright—a charming, gregarious businessman who also happened to be a giant fraud and criminal. The Bernie Madoff of his time, Wright was a financier/con man who bounced between England and New York bilking people out of their money by any means necessary—speculating in the silver, mining, and oil industries, seeking invest for numerous companies, selling shares to raise capital. He made millions, and lost it all, infamously and fatally swallowing a cyanide pill in court after being convicted and sentenced to seven years in 1904 for swindling investors. What’s more, a loaded revolver was found on his body. This was presumably to finish off the job if the cyanide didn’t work, but there has been speculation he originally planned to take out his accusers in court before turning the gun on himself.

Unsurprisingly, Macrory found Wright’s antics every bit as fascinating as his submerged hideaway, and in 2016 started writing a book about the swindler. The details he uncovered during a year of intensive research did not disappoint. Ultimate Folly: The Rises and Falls of Whitaker Wright, out January 8, is the result, and offers a much fuller picture of Wright’s dynamic life and robust story. VICE talked to Macrory to find out how the conman won and lost several fortunes, and how capitalism makes it easy for men like Wright to manipulate the system. Here’s what he had to say.

How did Whitaker Wright go from English preacher to becoming filthy rich in the new world?

He became a preacher to please his father, but he soon realized that the quiet life of an English minister would never satisfy him. He craved adventure and excitement, and he decided that the New World—the Wild West in particular—was the place to find it. A risk-taker by nature, he was prepared to face danger and hardship in his quest for riches. He was cunning and clever, and the gambles he took eventually reaped dividends, but only for a short time.

Why do you think Wright’s story is so uncovered in history? It seems like he’s only remembered for his underwater ballroom?

Wright left no diaries and no letters, and his immediate descendants didn’t like talking about him. Until recently, details of his life were sparse, and he tended to be remembered mainly for his unique underwater hideaway. Modern research tools—particularly the digitalization of thousands of local newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic—enabled me to fill in many of the gaps in his story. In this way I was able to present a far fuller picture of his extraordinary life then was previously possible.

Did his secrets destroy him?

Wright had many secrets. The biggest of the lot—known only to him for well over a year—was that his three main companies had become empty shells and were doomed to fail. If he had come clean straight away he might have salvaged something from the wreckage. Instead he delayed the inevitable by cooking the books. This had the effect of making matters far worse, and in that sense he was destroyed by his secrets.

Investors chased him from New York to England and then back again, did Wright think he could escape everything?

Wright was so rich and powerful that he probably believed nothing could touch him. He was genuinely amazed when detectives arrested him in New York in 1903. He told them it was all a misunderstanding and that he was ‘a friend of the king.’ He was sure that he would quickly be released, but the game was up and he was in for an unpleasant shock.

How was he finally apprehended, taken to trail, and sentenced to seven years in prison for his financial crimes?

The British authorities didn’t believe there was enough evidence to try him successfully and they refused to sanction a trial. Eventually a group of angry shareholders managed to raise enough money to fund a private prosecution. Wright fled to America, but a warrant was issued for his arrest and he was brought back to England. The case was heard in the Royal Courts of Justice in London in 1904. It was Wright’s bad luck that he appeared before a judge who was hostile to him from the start, and that he had to face a grueling cross-examination by one of Britain’s most brilliant prosecutors.

How did the media of the day treat his story and how much of your research consisted of reading old articles?

Until his downfall, the media of the day tended to give Wright favorable coverage. They loved a success story. On top of that, he had a number of corrupt journalists in his pocket. Not surprisingly, his death caused a sensation. The New York Times put it well: ‘Even in his life, which, with his rise from poverty to enormous wealth, was full of dramatic incidents, there was nothing that could compare with the manner of his death. All London tonight is thrilled with the news of it. No such human tragedy has been enacted in England for many a year.’ I read hundreds of such articles during my research, but I relied on many other sources as well. In particular I tracked down Wright’s great-great nephew who gave me access to a large archive of family papers.

How was Wright’s ultimate downfall as dramatic as his ascent?

The collapse of Wright’s companies was largely unforeseen and took place on the last trading day of the nineteenth century. It was a true fin de siècle moment. Thousands of investors were ruined or suffered huge losses, and 20 firms of London stockbrokers went under. The story was headline news. With masterly understatement, The Times of London commented that ‘the last settlement of the century has certainly terminated in a deplorable manner.’

Do you think capitalism makes it easy for men like Wright to manipulate the system to their benefit?

Wright played the capitalist system for all it was worth and the rules of the game—or rather the lack of rules—made it relatively easy for him. For instance, in the America of those days it wasn’t illegal to boost the value of a failing mine by dumping wheelbarrow-loads of silver-rich or gold-rich ore into it—‘salting the claim’ as the practice was called. In England, bizarre though it seems now, it wasn’t even an offense to produce a false balance sheet. Hardly surprisingly, Wright didn’t find it hard to manipulate the system to his benefit.

How would a man like Wright fair in today’s world and who could we compare him to in modern times?

Wright would have found it more difficult to succeed in modern times. He took advantage of loopholes in the law which have since been closed. On top of that, much of the financial press was corrupt, and he won favors from journalists by selling them shares on the cheap. That, hopefully, would never happen today. In my book I have compared him to Bernie Madoff in terms of his greed and shamelessness.

Was Wright more roguish hustler, conniving swindler or a mix of both?

He was undoubtedly a hustler, but I tend to think he wasn’t an out-and-out crook who deliberately set out to swindle people. Key to this is that he was a social climber who managed to become friends with the future king and other members of the British royal family. His position in society was important to him and he didn’t want to jeopardize that. Many astute observers of the time believed he was an essentially honest man who made a lot of money for a lot of people, and who only crossed the line into criminality towards the end of his career, and then out of desperation.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of VICE delivered to your inbox daily.

Follow Seth Ferranti on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.