‘Radio Commander’ Is an Intimate Look at War from an Uncomfortable Distance

Credit to Author: Rob Zacny| Date: Mon, 11 Nov 2019 15:45:31 +0000

Kovacs is on the radio in a panic. He says he’s being overrun by Vietcong, he has men down, and needs emergency evacuation. I’ve got the helicopters to get him out of there: Green Flight is only a kilometer away, but they’re medevacking wounded from another company that was engaged in some earlier fighting. Kovacs and his Alpha Platoon were sent there to bolster the perimeter to cover the evacuation. If I pull them out, the northwest perimeter is wide open.

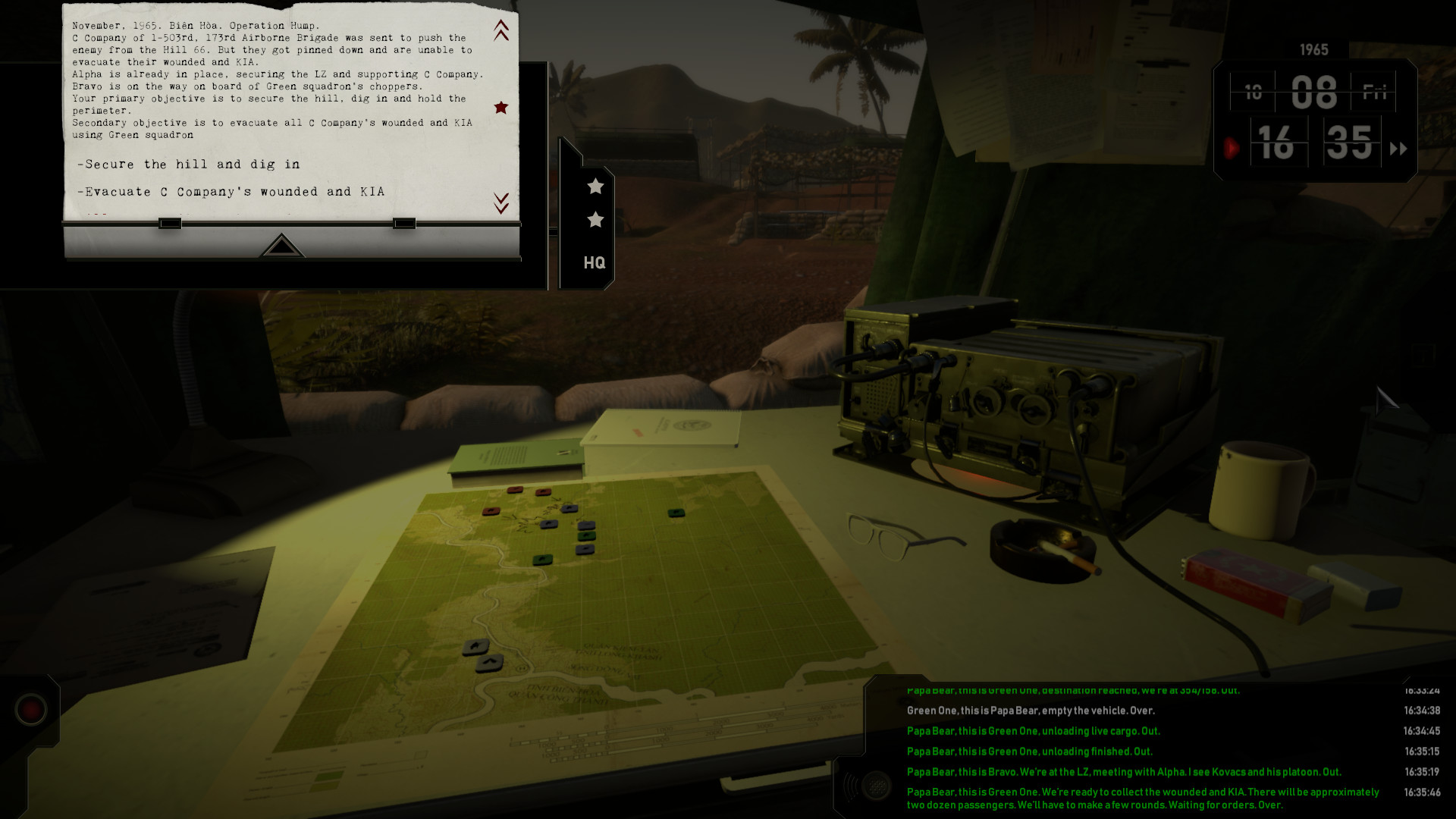

I can’t see any of this for myself. Radio Commander is a narrative wargame where you lead your troops through the early days of the Vietnam War from a distant command post. There are no hexes, no strength bars or combat odds tables that you can see. You have a radio, a list of callsigns that correspond to different units like infantry platoons, artillery batteries, and attack aircraft. You only know what they know, you can only see what they see. Even the map that you keep in your headquarters is merely a visual aid. You have to update it yourself as information comes in, marking out enemy positions as they’re reported, and drawing markers indicating where you have dispatched troops or fire support.

In this case, I ask Kovacs his status. A procedurally generated, stapled-together radio message comes back with his number of troops, wounded, ammunition level, and fatigue level. It’s a far cry from the panicked, scripted radio call of a few moments ago. Then I ask what enemy forces his platoon is in contact with.

About 30 or more Vietcong, plus the same sniper team that’s been harassing them all afternoon. Immediately I relax. Kovacs is defending high ground against an equal-strength Vietcong force. They’re unlikely to be overrun. I give the medevacs the go-ahead to continue their original mission. Alpha Platoon can fend for themselves for a few minutes while my artillery battery replenishes its ammunition supply and becomes available for another barrage. If things get dicey for Alpha, I can call in the big guns.

I don’t think I’ve ever played a game like Radio Commander. There have been other wargames that attempt to knock make-believe generals off the god-like perch that most games place them on, but few commit to that idea as much as Radio Commander. While there are simple 3D animations of life going on in the forward operating base outside your command tent, the vast majority of the game may as well unfold via text as you try and convert disparate reports into a coherent picture of the battle, and then send back the correct orders.

As daring as the idea is, Radio Commander still hedges its bets with units that respond instantly to prompts. A unit under fire will always be ready to send a full rundown of its situation, letting you track firefights almost blow-by-blow if you wish. Tell a unit to move, it’ll be underway within seconds. Commanders report exact coordinates for enemy positions, giving you easy targets for artillery and aircraft. Units don’t get confused even if you order a flurry of contradictory orders, and they always seem to identify who is who in the midst of chaotic jungle firefights. The only times I had to worry about friendly fire was with artillery and aircraft.

All of which means that Radio Commander routinely undermines the confusion and chaos it attempts to sow. Once you realize that your forces are still connected via radio like puppets on strings, Radio Commander becomes a far easier game than some wargames that have attempted to impose similar burdens on commanders. The toughest thing to deal with is the clumsy way in which you control your units, which sometimes crosses from novelty to annoyance as the game grows more complex and you’re coordinating multiple platoons, vehicles, and support units, feeding each of them X,Y coordinates about where to go and where to shoot.

An easy contrast here is Command Ops 2, which largely forces you to move individual units through subordinate commanders. You don’t just tell a tank company to blitz a crossroads and hold it against all comers, you tell their battalion commander to do it, and then attach instructions like how quickly or casualty averse they should be. Then the entire thing takes a while to execute as your broad instructions are filtered down into orders for each individual company and platoon leader. You can’t just get the soldiers at the tip of the spear onto the phone.

Command Ops is a very bookish simulation of 20th century combat command, of course, while Radio Commander is aiming to be something very different. Ultimately, it’s a wargame inspired by Vietnam movies like Platoon or perhaps most directly by A Bright Shining Lie, the HBO Bill Paxton movie about John Paul Vann’s journey from being a skeptical critic of the Vietnam War to one of its most ardent and effective prosecutors.

Like Vann, your character arrives in the early days of the United States’ involvement in the conflict and expresses a self-awareness about the nature of the counterinsurgency he is helping to wage. Your character is at pains to point out that the Vietcong likely have their own good reasons for fighting and the United States may not have a proper place in this war. From the early missions in 1965, where your forces are basically working to support South Vietnamese troops, you steadily take on a more direct role in an escalating war.

Unfortunately, Radio Commander can be pretty ham-fisted and overly influenced by Hollywood’s vision of the war. Vietnam and Vietnamese people remain somewhat abstract here. What the Vietcong and ARVN troops are fighting for and against is less important than the notion that it's not the right fight for American troops. After just about every mission, one of your subordinates will get on the radio and ask, “What was the point of this?” just in case the war’s eventual futility was unclear.

This clumsiness also makes its depictions of racism border on the offensive. We know that soldiers throughout history have resorted to racist slurs and stereotypes about their enemies, and it’d be dishonest to eliminate those words and the underlying racism from depictions of that history. But the way that slurs often come across in Radio Commander is as thematic seasoning on otherwise lackluster writing and performance, meant to signal that this is a game about the Vietnam War.

Even more sympathetic subplots have a tendency to come across like a war movie cliche. No sooner do you hear a black man with a southern accent on the radio than the character is introduced as “Preacher” and he goes into battle saying something like, “If you wanted to win this you shoulda just sent the black folks in from the start.” Meanwhile, Kovacs falls in love with a Vietnamese sex worker and isn't sure how to break things off with his sweetheart back in Texas (“You white boys,” the worldly Preacher huffs at him). You get a warning that an airstrike has been ordered in your area, and a few minutes later, one of your men describes a grisly scene as he comes to a burned village full of women and children. It’s not that these things don’t belong in a game about Vietnam, but they come so thick and fast that Radio Commander sometimes reduces itself to a series of tropes.

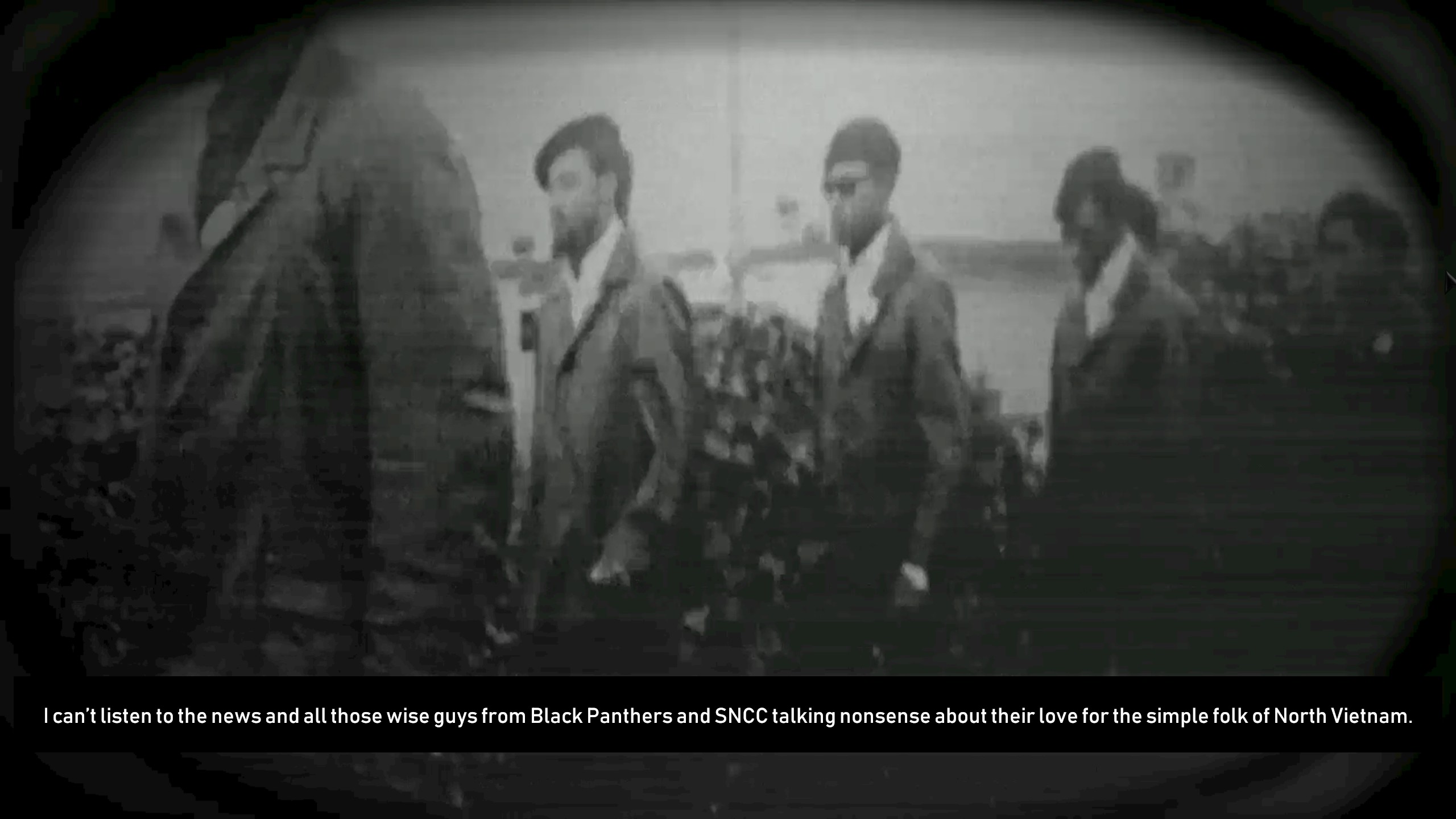

On the other hand, I admire Radio Commander’s narrative ambition as it attempts to tie together threads of context about Vietnam and its era. In a pre-mission cutscene, we learn that Preacher’s little brother has been thrown out of college for participating in increasingly confrontational civil rights protests, and both men have a deep cynicism about the United States’ and its purported values. Yet despite those letters home, Preacher’s fight for survival in Vietnam leads him to dehumanize his enemy as he increasingly sees every Vietnamese farmer and villager as a potential enemy to be killed.

Uncomfortably clunky and didactic writing undermine some of Radio Commander’s pretensions to being a game with Important Things to Say About War. But that doesn’t mean it’s not an important or fascinating game about war. While I don’t think its narrative lands, more wargames could benefit from trying to have a text with things to say beyond a comparison of the relative strength and position of two different sides. Its reimagining of how we might situate ourselves within a wargame, of how else we might depict the relationship between causes, commanders, and soldiers, is important and necessary in a genre that trends toward repetition and abstraction.

This article originally appeared on VICE US.